Key InsightBelly fat is more than a cosmetic issue. Visceral fat, which is stored deep in your tummy, releases inflammatory chemicals into your blood. This increases your risk for heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and chronic inflammation. Since you can’t see or feel visceral fat, measuring your waist is more important than tracking your weight alone. Even small decreases in waist size can improve your blood pressure, cholesterol, and insulin sensitivity in a few months. Knowing where your fat is stored helps you make changes that protect your long-term health. |

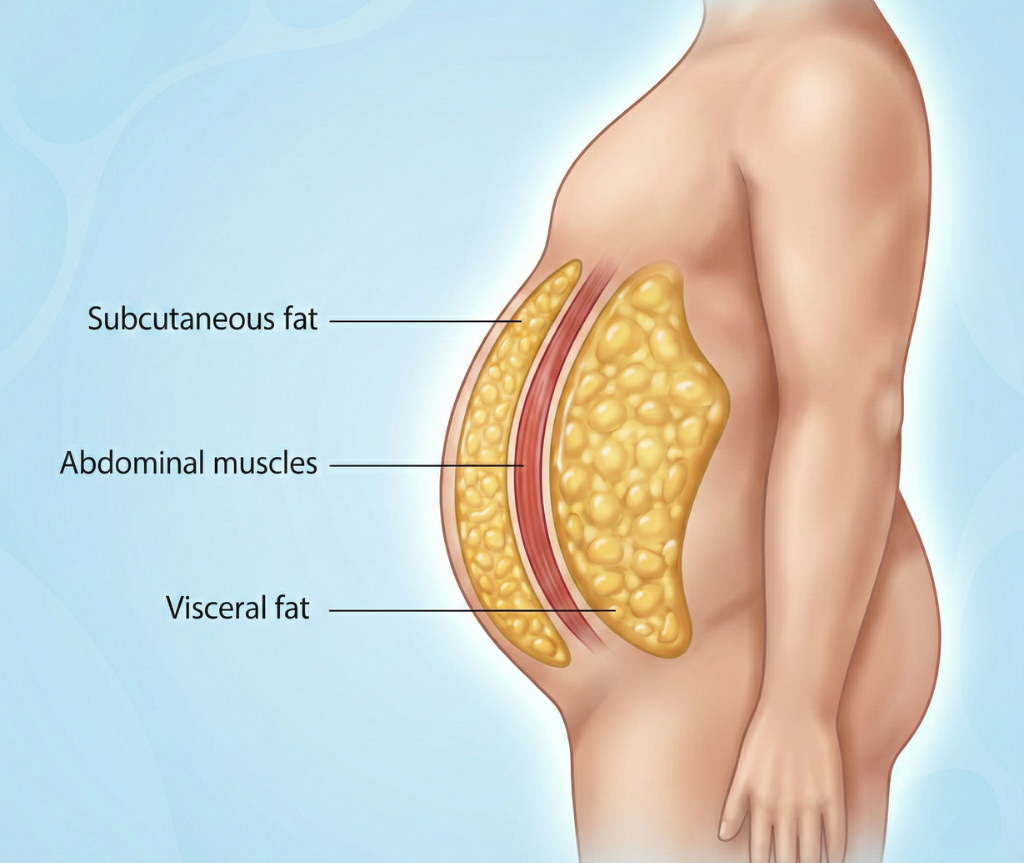

When you think of belly fat, you might picture the soft layer you can pinch. That’s called subcutaneous fat. Having extra isn’t great, but it’s much less harmful than the fat deeper inside.

Visceral fat is found inside your abdominal cavity, surrounding your liver, pancreas, and intestines. You can’t see or feel it from the outside. The problem is how it acts. Instead of staying still, it works like an active organ, releasing fatty acids, inflammatory proteins, and hormones into your blood.

Many people are surprised to learn that having too much visceral fat is a better predictor of metabolic disease than weight alone.

Two people can weigh the same but have very different health risks. If you carry most of your fat in your hips and thighs, your risk is lower than that of someone who stores fat deep in their abdomen. That person faces a much higher risk, even if the scale shows the same number for both of you.

How Belly Fat Damages Your Cardiovascular System

Your heart and blood vessels react to the inflammatory signals from visceral fat. These chemicals cause ongoing, low-level inflammation in your circulatory system. Over time, this slowly damages the lining of your arteries.

This damage appears in several ways. Your arteries become stiffer and narrower, raising your blood pressure. Your cholesterol levels change for the worse, and your HDL cholesterol, the ‘good’ kind, drops. Plaque can build up in your artery walls, which is called atherosclerosis. Your blood also becomes more likely to form dangerous clots.

Measuring your waist is one of the best ways to assess your risk of heart disease. Belly fat affects your cholesterol and how your body uses insulin. Even if your weight is healthy, having extra fat around your waist still increases your risk for heart issues.

The good news is that shrinking your waist can improve your heart health, even if you don’t lose a lot of weight overall. Your blood pressure may go down, and your cholesterol can improve within a few months. Where you lose fat is just as important as how much you lose.

The Direct Path From Belly Fat to Diabetes

Visceral fat has a direct effect on your blood sugar control. Unlike fat in your thighs or arms, fatty acids from belly fat go straight to your liver through a special vein. Once there, they make it harder for your liver to respond to insulin.

This starts a chain reaction. Your pancreas makes more insulin to keep up. Over time, your cells stop responding well to insulin. Your blood sugar slowly rises, often without obvious symptoms. Many people only find out through routine tests that they have prediabetes or type 2 diabetes.

Having too much belly fat is one of the strongest signs that you might develop diabetes in the future. It often matters more than your overall weight. If you carry extra fat around your waist, you’re also more likely to get metabolic syndrome. This means having high blood pressure, high blood sugar, and abnormal cholesterol at the same time, which greatly raises your risk for heart problems.

If you have a family history of diabetes or already have insulin resistance, your waist size is especially important. Genetics do matter, but how much visceral fat you have is also affected by your diet, activity level, and sleep. You have more control over this than you might realize.

Inflammation: The Hidden Thread Connecting Belly Fat to Multiple Diseases

Chronic inflammation is one of the biggest hidden dangers of visceral fat. The fat around your organs makes molecules called cytokines, which keep your immune system on high alert. Unlike the short-term inflammation that helps you heal, this low-level inflammation can last for months or years and quietly damages tissues all over your body.

This constant inflammation can cause problems you might not link to belly fat. It can speed up joint wear, raise your cancer risk, affect your brain function, and make you more likely to have autoimmune flare-ups. It also slows your recovery from illness and may lead to memory problems as you get older.

The link between inflammation and belly fat works both ways, making it harder to break the cycle. Inflammation leads to more fat building up around your abdomen, and the longer this goes on, the tougher it is to stop. That’s why losing belly fat often improves many health markers at once. You’re not just losing weight—you’re also reducing a major source of inflammation.

Stress, Sleep, and the Stubborn Nature of Abdominal Fat

Cortisol is your main stress hormone. When it stays high, it causes your body to store more fat in your belly. Ongoing stress, lack of sleep, or irregular eating habits all keep cortisol levels up. As a result, your body stores more calories as belly fat instead of burning them.

This sets up a frustrating cycle. Stress leads to more belly fat, and belly fat upsets the hormones that help you handle stress. Not getting enough sleep makes things worse. When you’re tired, your cortisol rises, your appetite grows, and your body becomes less sensitive to insulin.

Improving your sleep can help reduce visceral fat, even if you don’t follow a strict diet. Both how long and how well you sleep are important. Managing stress to lower cortisol can also shrink your waist. Regular exercise, meditation, and spending time outside all help.

If your belly fat won’t budge no matter what you do, check your sleep quality and stress levels. Sometimes the issue isn’t your diet or exercise, but that your body can’t respond well when it’s under constant stress.

Why Your Waist Measurement Matters More Than You Think

A bathroom scale can’t show you where your fat is. You could lose five pounds of muscle and gain five pounds of visceral fat, and the scale would stay the same.

Measuring your waist is a simple way to estimate belly fat, and it’s closely linked to your real health risks.

Your health risk goes up when your waist is more than 94 centimeters (37 inches) for men or 80 centimeters (31.5 inches) for women. The risk keeps rising as your waistline increases.

These numbers are general guidelines, not strict rules for everyone. Your personal risk depends on many factors, such as your ethnicity, muscle mass, family history, and any health conditions you have.

Some people, such as those with polycystic ovary syndrome, fatty liver disease, or metabolic syndrome, may be at higher risk even with a smaller waist. If you’re unsure about your risk, ask your doctor for advice that fits your situation.

Measuring your waist correctly is important. Use a flexible tape measure just above your hip bones, at your belly button level. Take the measurement at the end of a normal breath. Don’t pull the tape too tight or suck in your stomach. Track your measurements over time rather than focusing on a single number.

Practical Approaches That Actually Reduce Visceral Fat

The good news is that visceral fat often goes down quickly when you make healthy lifestyle changes. Since it’s metabolically active, it’s usually the first to decrease when you improve your diet, get regular exercise, and sleep well.

- Being active is one of the best ways to lose belly fat. Activities like walking, cycling, and swimming help burn fat in your abdomen. Lifting weights or doing resistance exercises builds muscle, which helps your body use insulin better and keeps your metabolism up, even at rest. You don’t have to spend hours at the gym—being consistent is more important than working out really hard.

- Try to eat in a way that keeps your blood sugar steady all day. This usually means eating more fiber-rich vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats, while cutting back on processed foods and added sugars. When you eat can also matter—irregular meal times can disrupt your body’s natural rhythms and lead to more belly fat.

- Sleep is just as important as diet and exercise. Aim for 7 to 8 hours each night and try to keep your sleep and wake times regular, even on weekends. Poor sleep can disrupt the hormones that regulate appetite and fat storage, making it harder to lose belly fat, no matter how well you eat or exercise.

- If you take medicines that affect your metabolism, check with your doctor before making major changes. Some drugs, like corticosteroids, certain antidepressants, and diabetes medications, can change how your body stores fat.

- Health conditions such as hypothyroidism or Cushing’s syndrome also affect fat storage. Your doctor can help you set realistic goals and adjust your plan as needed.

Moving Forward With Realistic Expectations

Knowing why belly fat is a real health risk can help you focus on preventing disease, not just on looks. Gaining visceral fat isn’t a personal failure or a sign of weak willpower. It’s your body’s response to stress, poor sleep, inactivity, and diet over time.

When you change these habits, your body will adjust. Progress might feel slow, especially if you’ve had extra belly fat for a long time. But even small drops in waist size can bring real benefits. Your blood pressure may go down, your insulin sensitivity can get better, and your inflammation can decrease. These improvements often show up before you notice big changes in the mirror.

Your daily choices have a big impact on these results. Progress comes from being consistent, not perfect. Focus on building one healthy habit at a time.